Exercise Availability Disorder (EAD) is Literally Hurting Your Athletes

Derek M. Hansen - August-September 2023

Fear-mongering is one of the best ways to get people’s attention these days. It’s being used effectively by all groups – most notably, politicians, economists and virologists – so why not take full advantage of this phenomenon when advising strength and conditioning coaches, fitness experts and rehabilitation professionals. Calling something a ‘disorder’ is also a good way to formalize and articulate a problem in society. So now that I’ve got your attention, let’s get down to business.

I’m going to come out and say it right now. I believe there are far too many exercises out there, and it is creating a problem for both athletes and the general population. Injuries are continuing to rise at unacceptable rates in both of these groups, and it is debatable if any performance improvements we are seeing are the result of savvy exercise programming versus general technological advances. What is absolutely clear to me is that people love new exercises. Novelty creates enthusiasm and, perhaps, a perception of innovation and progress. Social media channels are pandering to this weakness in people and new exercises are being developed every day to satisfy the dopamine addiction in everyone’s brain. And, 99% of these new exercises are being invented and promoted by people who have no business creating exercise. We need new exercises like we need new podcasts, new influencers, new diets, new life coaches and new OnlyFans accounts.

Perhaps the exercise selection craze started back in the early days of modern bodybuilding, when Arnold Schwarzenegger was claiming that pumping up a muscle was comparable to an orgasm. Maybe people thought that having more exercises was like having new sexual positions or multiple partners. Muscle magazines, who were actually just peddling supplements, had a vested interest to create more exercises to bundle with protein powders and energy shakes as their magic solution. New exercises, combined with new supplements and diets, was always going to be the answer, regardless of the question or the audience.

In modern times, we see the same affinity for an abundance of exercises as the solution to our fitness and athletic performance goals, with strength and conditioning experts constantly pushing their exercise solutions for sporting success, as well as rehabilitation professionals advocating for their own series of prehab and rehab exercises. Equipment manufacturers are jumping on the exercise selection bandwagon whether it is the creation of new resistance machines or complementary technologies that collect ‘valuable data’ for coaches. Just like the early bodybuilding exercise promoters, money has been the driving force behind these so-called innovations, preying on the insecurities of both coaches and athletes. Fear of missing out (FOMO) seems to be motivating behaviours more than a search for the truth and achievement of quantifiable results. As such, “Top 10 Gym Exercises for _________” seems to be one of the more popular search engine query.

Exercise Dilution Outstripping Physical Adaptation

There have been two phenomenon that I have seen personally that have shown me that many coaches today believe that an abundance of exercises in a workout session is a hallmark of an effective training program. The first is the development of online training platforms that allow coaches to ‘build’ programs in a thoughtless manner, simply creating a shopping list of items that looks visually impressive (and complete) but lacking in the precision and organization required to create lasting adaptations that progressively build to greater abilities. Dragging and dropping exercises to fill a menu makes it too easy to diverge from what is needed: boring consistency and repetition.

When you add more exercise to a program and an athlete does not have significantly more time to implement all of these exercises, something has to give. In many modern training programs that have come across my desk, I have found that there is less reliance on a multiple set approach. Because there are more and more exercises, the number of sets has decreased. Time and repetition has been squeezed by the proliferation of exercises. Whereas I may have programmed 5 to 6 sets of 3 reps for an explosive or maximal strength exercise, I see now that coaches are opting for 1 or 2 sets of higher rep ranges in order to satisfy volume requirements. Whereas, I was trying to accumulate both volume and intensity, maximal effort and intensity seems to have been thrown out at the expense of volume in this example.

Adding more exercises may seem like a prudent approach to the casual observer, since the athlete is being exposed to a wider variety of stimuli. However, I know from experience that multiple sets allow an athlete to develop greater skill at an exercise, but also improve overall readiness and potentiation as part of the multiple-set journey. It may take an athlete 3 to 4 sets before they are truly firing on all cylinders and able to push beyond their limits. Focusing on fewer exercises and gaining mastery and momentum can have a tremendous impact on an athlete’s physical and mental development over time. Adding more and more exercises can result in an athlete never getting off the ground, diluting any momentum gained within a larger range of progressive sets.

Thus, the second phenomenon I have commonly seen is that ‘variety’ and ‘variability’ are championed as a necessary quality in a training program. While there are good reasons to vary up exercises, velocities, sets, reps and recovery periods, gains in performance can only be consolidated after consistent application of a planned stimulus over time. Time and repetition allow for the organism to experience sustained stress in a specific manner. Infusion of too much variety can disrupt this process, with the chronic training load being interrupted and limited benefits carrying over. Are shortened exercise attention spans limiting the efficacy of all training activities, with no sustained efforts being achieved long enough to consolidate training gains and influence retention of skill and capacity? If excessive exercise ‘variation’ has the potential to dilute an athlete’s adaptation abilities, how do we bring the coaching world back to boring repetition of a few tried and true exercises?

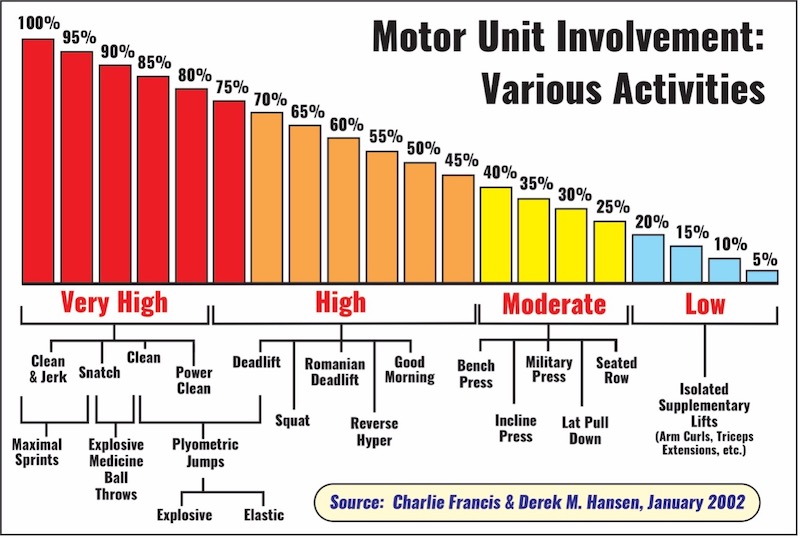

The “Motor Unit” Graphic

Figure 1 below illustrates one of the more popular graphics ever published around exercise selection and motor unit involvement. How do I know this? Well, every time someone uses it in a presentation or posts it on social media, very rarely do they quote the source and I quickly receive a text or email about it. And, let me tell you – there have been thousands of messages sent to me about this diagram. Thus, I have taken the liberty to add in the source information within the diagram, knowing full well that it can easily be ‘Photoshopped’ out by the next plagiaristic vulture. But I digress…

I was fortunate enough to be in the dining room of Charlie Francis over twenty years ago to participate in the creation of this diagram. The process was not about pulling data from research papers – as no research had been performed in this area and has yet to be investigated. Charlie simply presented a concept to me which demonstrated that sprinting was one of the most centrally and peripherally intense activities that could be performed and then asked, “Where do you think other training activities fall along the motor unit spectrum based on your knowledge and experience as both an athlete and a coach?” We spent the next few hours putting together an array of activities that we felt best represented the relative stresses imposed on the athlete population, particularly elite sprinters.

Figure 1: Motor unit involvement over various training activities

But let’s be clear: This diagram – as presented – must be applied to a population that has been appropriately trained in the majority of these activities and possesses a base level of skill and athletic ability in order to generate enough stress on the body and brain to create a positive – and for the most part, systemic – training adaptation. If you lack the mechanics or power to sprint properly, sprinting as training activity may move significantly to the right of the diagram. Similarly, if you have had no instruction on Olympic weightlifting movements, cleans, snatches and jerks may be much less effective than deadlifts, squats or bench pressing in activating motor units and impacting the central nervous system (CNS). If you have are a 12-year-old athlete with no weightlifting experience, push-ups, jumping jacks and using a skipping rope may have more of an impact on your athletic ability than anything that can be accomplished with a barbell in the short term. Having a relative understanding of what will improve a given individual’s athletic abilities is extremely important for a coach or rehabilitation professional.

The whole point around the creation of this graphic was to explain to coaches that there are a number of options available to them when creating a training program, all of which require careful and special consideration. The uninformed and naive will simply throw exercises together in their training programs only thinking about the positive benefits of individual exercises and not understanding that there is a finite amount of energy and resources available to convert those exercises into useable adaptations that move an athlete forward with their performance abilities. This would be akin to an untrained, self-proclaimed ‘chef’ throwing all of their favourite flavours and ingredients into a pot with the expectation that something marvelous would eventually hit their tastebuds, only to find out later that only their gag reflex had been highly stimulated. More is not better. Better is better.

The educated and experienced coach will choose their exercises wisely and only select those that make sense for a particular session, week or phase of training given the context of the situation including the athletes involved, the time of the year, the training history and the overall goals of physical preparation. There is a desired effect their athletes will derive from that particular exercise – either specifically or generally – that fits into the overall plan. It is not about throwing everything against the wall to see what sticks. There are compatibilities and synergies that must be taken into consideration.

I once heard a coach in a presentation – using our infamous ‘motor unit’ diagram in a slide without crediting us – say that this diagram essentially told him that if he wanted his athletes to be fast and powerful, they should simply train all of the activities on the left side of the diagram and do less of the exercises on the right of the diagram. Experienced and knowledgeable coaches understand that many of these activities can only be trained effectively if they are not directly competing for central nervous system energy. Proper periodization of training activities ensure that different activities are trained on separate days or in different phases in order to maximize their effectiveness and not create exercise redundancies that rob the athlete of available energy and interfere with desired adaptations. Exercises on the right can still be effective in precisely building local work capacity or hypertrophy, filling in gaps where higher intensity activities could possibly lead to burnout.

For example, Olympic weightlifting activities and sprinting both require a vast amount of human resources in order to be maximized. Performing full clean and jerk movements would not be common in the preparation of a world class sprinter because of this fierce competition for available energy. There may be phases where power cleans or power snatches are used in preparatory phases to build power and assist with starting and early acceleration abilities. This work may correspond nicely with shorter sprints over 10 to 30 meters. But changes will have to be made in order to accommodate new demands and qualities as a training program progressed, and greater sprinting outputs were required.

As an athlete begins to hit maximum velocity territory in their sprint work, resources have to be diverted to this activity at the expense of other activities. Hence, only derivatives of the full movements may be used, such as cleans or snatches from blocks or a hang position. Other coaches may move into more basic movements such as squats, deadlifts or presses that do not consume as much central nervous system energy, while preserving overall preparedness qualities developed earlier in the training program. Velocity of movement is handled by the maximal sprint work, while recruitment is maintained by basic weightlifting movements. But a trade-off must be achieved and exercises may need to be stripped away in the training program.

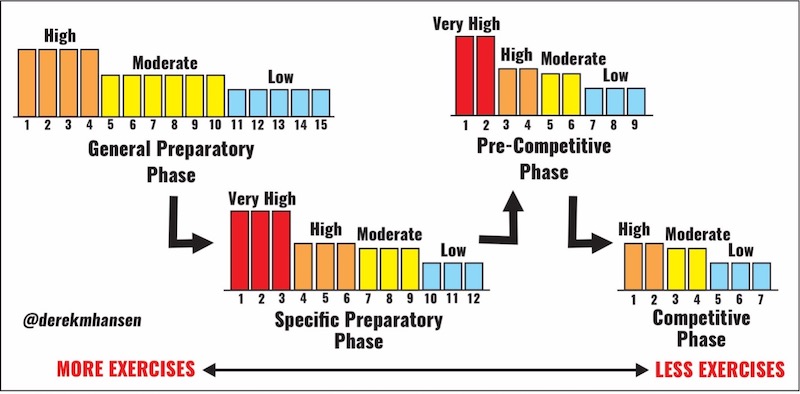

Generally, as depicted in Figure 2, the number of exercises in a training program will decrease over the course of a training program, as specific competition demands increase in volume and importance. A higher number of low-to-moderate intensity exercises are typically used in a General Physical Preparatory phase with low work-to-recovery ratios for general fitness purposes and dispersing a moderate stimulus over many different body parts and muscles. As the athlete progresses closer to competition, higher intensity exercises can be used, with a reduction in the total number of exercises to conserve energy. In the latter phases of a training program, even more exercises are stripped away to make room for the specifics of a sport, position group or event. Some combination of high, moderate and low intensity exercises can be retained, but the total number of exercises must be reduced to allow specific skills and abilities to flourish at a competitive level.

Figure 2: Progression of exercise utilization over the course of a training program

Thus, as the energy envelope expands for the introduction of specific, high-intensity activities such as maximum velocity sprinting, overall exercise variety and number must contract. This may also be the case for the necessary sport-specific activities such as practice and game play during an in-season period. Exercises used to complement these activities must be chosen careful to ensure that athletes are supported, but not exhausted and overloaded. ‘Sport-specific’ exercises outside of regular practice are not necessary and can be detrimental to joints and connective tissues. Things may get boring and repetitious in order to maintain health and performance, but fancy exercises are not required to maintain general fitness qualities in an elite athlete, despite what you may have heard. Simplicity reigns supreme as you move up the ladder of performance. Everything else is window dressing.

The Folly of Using Singular Exercises to Solve Multi-Factorial Problems

The great thing about social media is that you can get a simple message out to a broad audience in a very short amount of time for relatively little cost. The worst thing about social media is that you can get a simple message out to that same broad audience in a very short amount of time for relatively little cost. We see this every day in its best and worst forms. Someone is pushing a single exercise – or a type of exercise – as the saviour for all the horror that afflicts the human race. In the high performance realm, it is usually one exercise to prevent a specific injury or another exercise to make you jump higher or run faster. But the offer is always the same: “Do this, trust me and everything will be fine… and make sure you subscribe to my channel!”

While we would all like to find that one exercise that solves all of our problems, those in the know actually understand that a systematized arrangement of work in many different areas yields the best results that are durable over time. The problem is that the ‘magic bullet’ phenomenon is compounded by the continuous addition of magic bullet after magic bullet until a junk-pile of magic bullets fills your training program, and you end up wondering why your bullet collection is so large, when you could have been practicing your shooting accuracy all this time. What must be understood is that there is a critical mass of exercises that must be maintained from week-to-week, phase-to-phase and year-to-year. Too few exercises can be just as much of a problem as too many exercises in a training program. Balance is key.

One of my favourite quotes from legendary college basketball coach, John Wooden, is, “The worst thing about new books is that they keep us from reading the old ones.” We could easily say the same thing about exercises. New exercises should not automatically take the place of valuable and effective older exercises. Hence, it does raise the issue of the need to regularly audit your training program to determine which exercises need to be retained for continued performance and health improvements, and which exercises can be eliminated altogether. Every coach will have a different method of evaluating exercise efficacy. The important point here is that a process should still be in place to make sure a regular evaluation is scheduled, and perhaps reviewed with a team of coaching peers so that the evaluation is unbiased and professional in scope. The key message here is that you have to work hard to justify your exercise selection. Exercise audits should not be a quick and easy process akin to the quick swiping motion involved in modern online dating.

Being Boring is the New ‘Innovative’

I often challenge young coaches to dare to be boring. I tell them that I need them to get better at doing the same thing over and over again. “Mastering boring will make you a better coach,” I tell them. I may give them a simple sprint workout such as 3 sets of 4 x 20 meters and instruct them to repeat it over a four week period, two times per week. I allow them to make adjustments to intensity, rep recoveries, set recoveries, start types and body emphasis. In one week you can use longer recovery periods. For another week you can switch shorter rest breaks. Some workouts may involve only an emphasis on arm mechanics, while others will direct the focus to quick and powerful ground contacts. Very slight adjustments can yield significant improvements, while the consistent exposure to essentially the same type of work can build capacity, skill and resiliency. This can be done for any training element including weightlifting, plyometrics, flexibility and endurance. However, changing the workout significantly and adding different exercises in an effort to pay lip service to 'variety' may disrupt that steady accumulation of a familiar but effective chronic workload.

Essentially, we are combining a consistent – albeit boring – approach with nuance. This is what great coaches do well. They thrive on the implementation of slight adjustments here and there, as opposed to introducing sweeping changes in exercises and workloads. Those that are patient and deliberate with their nuanced approach will reap the benefits over time, and also experience significant retention of those benefits over the long term. Bruce Lee is famous for saying, "I fear not the man who has practiced 10,000 kicks once, but I fear the man who has practiced one kick 10,000 times." This same approach can be applied to virtually any exercise, reserving an athletes exposure to only those exercises that yield the greatest contribution to their performance and health.

Variation in exercise selection can be introduced periodically as a novel means of refreshing the brain and body, but not applied as a prime driver of adaptation and physical development. Re-introducing coaches to the concept of being painfully consistent with their application of exercise stimulus and chronic workloads can be a difficult discussion, particularly in a time where athlete attention spans are diminishing from minutes to seconds. Entertainment must not be the motivation for making programming changes. Tapping into your own personal enthusiasm, charisma and storytelling abilities may be the most useful coaching skill that you develop over your career in order to avoid the pitfalls of settling for exer-tainment over proper training. Your presence and delivery need not be boring. Save that for your exercise selection.

Concluding Remarks

While it is easy to come off as that ‘old guy yelling at clouds’ or ‘telling kids to get off your lawn’ when complaining about the proliferation of new exercises (or new music for that matter), the main thrust of this article is that everyone needs to perform annual maintenance on their training programs and overall exercise philosophy. As I mentioned previously, formally or informally auditing your approach with exercise selection on a regular basis is a worthwhile investment. Exercise hoarding and over-consumption does not lead to sustained improvements at any level.

If you are able to prioritize exercises based on both their potential specific and general contributions to a sport or activity, and then generate a list of key exercises for every phase of your training program – factoring in the time available, technique/skill requirements and equipment needed – you should be in a good position to assemble an effective plan. However, I must emphasize that this process must be driven by absolute need. You cannot and should not add exercises on a whim after seeing them presented at a conference, seminar or course, let alone a social media post. There must be a vetting process and even a discussion and debate amongst trusted peers. And, if your vetting process identifies potential efficacy for a given exercise, you must then decide if another exercise or group of exercises must be removed or reduced in involvement to make room for the new addition. Find your critical mass even if it be through trial and error.

This exercise evaluation process is part of your evolution as a coach. The hardest thing for a coach is to – as Bruce Lee was quoted as saying – “Discard what is useless,” as we are all so good at collecting stuff. Also keep in mind that we are all not perfect and many a time I have had to re-introduce older exercises that I discarded decades before because I became enamoured with ‘new techniques.’ Many of these discarded exercises were basic (and boring) in nature, but served a significant purpose in the development and maintenance of key fundamental qualities. The wisdom in understanding these significant contributions may only come with age, the passing of time and the accumulation of knowledge. If you are able to combine your youthful exuberance with a patience for learning and keen observation skills, you will be able to arrive at a collection of exercise that provide sustainable maximal returns.